To the few people who have dropped by here in the past year in hopes of finding something new to read: My apologies. I was originally planning to use this blog to update my family and friends on my experiences in South Africa, but then found an easier (but much more annoying) method in line with infrequent Internet access: mass e-mails.

However, after two weeks of nationwide school strikes and a week of recuperating from an ACL injury suffered from an foolish leap off the back of a pick-up truck in front of a crowd of Venda women watching a traditional dance video outside the TV store in Thohoyandou -- I am finding myself with way too much time on my hands. In my case, this means there is way too much thinking going on inside my head which I can't discuss with my host family because I can't speak Tshivenda well enough (even if I could, brooding is not a common preoccupation in this part of the world). But I do have a laptop, keyboard and a memory stick. Ahh, you lucky readers!

I am missing school these days. Not the corporal punishment that teachers mete out when they think I am not watching or the hours of waiting to accomplish one small task because someone is late or has lost the proper paperwork, etc, etc. Mostly I miss the kids.

I have to admit that I enjoy the way the grade R learners (kindergartners) chant my name in unison when I visit their classroom or the way kids of all ages will continually shout my name on the playground until I acknowledge them with a smile or wave. I can see how movie stars can get used to constant attention and come to expect it after a while. Are you still real if someone doesn't recognize you?

But the attention isn't the only reason I miss those little buggers. It's the way they are all so eager to be at school, the joy on their faces when they are asked to do even the smallest thing -- like write on a chalk board, the way they are so generous with each other, sharing their lunch or a pencil with someone who doesn't have one. It makes for a wonderful, affirming work environment.

I'm not lonely though. The house is filled with people ALL the time -- Vho Maggie, Awelani, Thihangwe, Vho Mammburu, Mudalo, Rose, Vho Nyadzanga, various visiting relatives and friends. Awelani and Rose brought bathwater and meals to me just after my injury when I couldn't walk. And the kids in the neighborhood are also keeping me company -- picking objects off the table in my room and asking "is this?", eating it if it is food, drawing on their arms and legs with it if it is a marker or eyeliner, making pretend cellphone calls with it if it is anything else, playing with great imagination and energy, occasionally hitting my injured knee on purpose to make sure I am still in pain, being cute.

But I also miss being busy -- having a busy daily schedule, many things to do, places to go, papers to shuffle and organize. When I was at the Peace Corps office in Pretoria for x-rays and stuff last week, I was so envious of the staff and their ringing phones and official-looking desks with crammed in-boxes.

Sure I have things to do here -- complete plans for the high school peer counselor camp in July, complete an application for a well for one of the schools, plan an upcoming vacation to the Grahamstown Arts Festival and a week along the Wild Coast. But none of it seems official enough or of urgent necessity.

As I write this, I see how ridiculous I am, missing what I don't have and not wanting what I do have. If I was in school, I would be complaining that I wanted more time to rest my leg and plan my vacation. While working three jobs at the same time just before I left the states, I was dreaming of simplicity in a rural environment. I have so much. Feeling dissatisfied is really just a bad habit.

Monday, June 18, 2007

Sunday, May 20, 2007

The Mochakis, one of the families I stayed with when I first arrived in South Africa had a ceremony one evening to honor their ancestors. The kids and I were not permitted to witness the actual events taking place in the darkness outside the house that night, but we heard the rattle of stones tossed onto each corner of the tin roof and, the next morning, saw a calabash laying in a small hole in the ground by the door where Damaris told me that home-brewed beer had been poured as a gift to the family members who have passed away.

While ancestor worship has not been ritualized in my culture, it is still present in its own way. And it makes wonderful sense to me.

So many people who have guided me in my life are now gone from it. Yet, when I am still, quiet and open, their wisdom and love fills me -- in quantities so great it is clear that death has not silenced them completely. They are my personal cheering squad.

Mom, Dad, Dede, Grandaddy, Uncle Paul, Aunt Marie, Uncle Harold, Aunt Alice, Uncle Ed, Patti and others. During my nearly two years in South Africa, I have felt them all here with me at some time or another -- as calming as a father-sized hand on my head, as strengthening as an embrace from familiar motherly arms, as loving and accepting as doting grandparents, aunts and uncles.

Perhaps it is they who whisper words of joy disguised as children's squeals of delight, heat-soothing winds and bird calls. Or who draw my attention to an inspirational paragraph in a book I have just opened, offer examples of strength in the form of elderly women carrying bundles of firewood down the mountain and who provide difficult people and obstacles to teach unconditional love, endurance, patience, contentment.

I was strongly aware of the presence of my ancestors one day during my first week in this country. Missing my Dad, who had died only a month prior, and overwhelmed by a sense of not belonging, I went to a sandy spot under a big tree and just let the tears flow. Silently, I asked Dad for help, as I would have if I could have called him on the phone.

There was no sudden voice from above or a lightning bolt, but after sitting for about 10 minutes, I became aware of the birds in the tree and there came an overwhelming sense of peace. It was the same way I felt when my father would say to comfort me during difficult moments: "You're OK kid. Daddy loves you." It was enough.

Acknowledging such gifts from my family members (including the non-biological ones), what they offered when they were alive and what they continue to give after their death, is necessary -- even if I choose not to do so with a gourdful of African beer. It reminds me that what I am and what I have yet to become, is never, ever achieved alone.

While ancestor worship has not been ritualized in my culture, it is still present in its own way. And it makes wonderful sense to me.

So many people who have guided me in my life are now gone from it. Yet, when I am still, quiet and open, their wisdom and love fills me -- in quantities so great it is clear that death has not silenced them completely. They are my personal cheering squad.

Mom, Dad, Dede, Grandaddy, Uncle Paul, Aunt Marie, Uncle Harold, Aunt Alice, Uncle Ed, Patti and others. During my nearly two years in South Africa, I have felt them all here with me at some time or another -- as calming as a father-sized hand on my head, as strengthening as an embrace from familiar motherly arms, as loving and accepting as doting grandparents, aunts and uncles.

Perhaps it is they who whisper words of joy disguised as children's squeals of delight, heat-soothing winds and bird calls. Or who draw my attention to an inspirational paragraph in a book I have just opened, offer examples of strength in the form of elderly women carrying bundles of firewood down the mountain and who provide difficult people and obstacles to teach unconditional love, endurance, patience, contentment.

I was strongly aware of the presence of my ancestors one day during my first week in this country. Missing my Dad, who had died only a month prior, and overwhelmed by a sense of not belonging, I went to a sandy spot under a big tree and just let the tears flow. Silently, I asked Dad for help, as I would have if I could have called him on the phone.

There was no sudden voice from above or a lightning bolt, but after sitting for about 10 minutes, I became aware of the birds in the tree and there came an overwhelming sense of peace. It was the same way I felt when my father would say to comfort me during difficult moments: "You're OK kid. Daddy loves you." It was enough.

Acknowledging such gifts from my family members (including the non-biological ones), what they offered when they were alive and what they continue to give after their death, is necessary -- even if I choose not to do so with a gourdful of African beer. It reminds me that what I am and what I have yet to become, is never, ever achieved alone.

Wednesday, March 07, 2007

The neighborhood kids and I are hooked on Nollywood soapies. My host family has DSTV (lucky for me) and one of the channels, 102 -- known as Africa Magic -- runs Nigerian dramas for most of the day, every day. So many afternoons, after the kids and I are out of school, they will quietly slip into the house and congregate on the floor in front of the television. One of them, usually Phuluso, the oldest (10) will whisper "Sheila, 102!. 102!" And soon we are watching shows like "We Are But Pencil in the Hand of the Creator."

The things that movie snobs would deride in Nigerian films are what I love: overly dramatic scenes with the same, predictable scary music ("dum dum DA!"), goofy romantic scenes with the same Whitney Houston songs or really bad made up love songs ("I just love you, because I just love you") and the episodes about witchcraft where the simplistic special effects are no better than what was used in the Dr. Who series.

Maybe I like Nollywood dramas because they remind me of some of my earliest TV obsessions. I must have been no more than 6 when I hung out with the neighbor kids and their mom in the early afternoon, watching Days of Our Lives and Dark Shadows. But I still recall sitting with them in front of the tv in the master bedroom and anticipating that moment when a serious male voice would intone: "Like sands through the hourglass, so are the Days of Our Lives" followed by the swell of romantic theme music. And I remember being creeped out by the evil deeds of vampire Barnabas Collins, but being unable to stop watching Dark Shadows.

I wonder if, years from now, Phuluso, Vhuthu, Mishumo and Vonnguali will feel equally nostalgic about the sound of Whitney Houston and bad special effects.

The things that movie snobs would deride in Nigerian films are what I love: overly dramatic scenes with the same, predictable scary music ("dum dum DA!"), goofy romantic scenes with the same Whitney Houston songs or really bad made up love songs ("I just love you, because I just love you") and the episodes about witchcraft where the simplistic special effects are no better than what was used in the Dr. Who series.

Maybe I like Nollywood dramas because they remind me of some of my earliest TV obsessions. I must have been no more than 6 when I hung out with the neighbor kids and their mom in the early afternoon, watching Days of Our Lives and Dark Shadows. But I still recall sitting with them in front of the tv in the master bedroom and anticipating that moment when a serious male voice would intone: "Like sands through the hourglass, so are the Days of Our Lives" followed by the swell of romantic theme music. And I remember being creeped out by the evil deeds of vampire Barnabas Collins, but being unable to stop watching Dark Shadows.

I wonder if, years from now, Phuluso, Vhuthu, Mishumo and Vonnguali will feel equally nostalgic about the sound of Whitney Houston and bad special effects.

Saturday, October 14, 2006

In the Internet cafe in Makhado, a formerly all-white city in northern Limpopo, an Afrikaner boy next to me is playing a computer game with realistic graphics based on the movie Blackhawk Down (about a military shoot-out in Somalia). He's about 10 years old with that sweet baby calf awkward wide-eyed innocence, shaggy blonde hair cropped close to his head. His mouth hangs wide open in concentration and his big eyes are focused solely on the screen where a machine gun he controls blasts away at any black-faced villager that runs out from a compound of decrepit buildings. The overt violence of the game, the age of the boy playing it and its racial implications disturb me greatly. The appearance of the village and some of the villagers are similar to what I see in rural South Africa. But what is most disturbing are the American flags on the uniforms of the armed soldiers who rush out into the village to support the machine gun. It's a game, yes. And to win it, the fictional American soldiers, along with the young boy playing the game, must kill.

Thursday, October 12, 2006

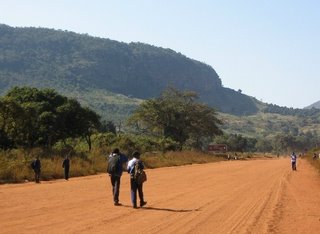

In a year or less, Tshifudi Village will no longer look quite like this. Work has begun to pave over the dirt road. While a tar road will greatly assist transportation in the area, especially during the rainy season, I can't help but feel a little wistful at what will be lost. Sleepy little Tshifudi will certainly be sleepy no more.

Wednesday, August 16, 2006

Random stuff from my village:

- Several people have told me that the light skinned babies are referred to as "Sheila's children."

- Today I rode in the most decrepit taxi I have ever seen. Probably made in 1970s (red vinyl seats, altho with springs coming through). Rust and dents everywhere. Holes in floor. Sticker on dash read: "It's All in God's Hands."

- The employees of Shoprite, the only supermarket in the big city of Thohoyandou, were protesting (AKA here as "toyitoying") outside the store. Mostly dressed in cheery Shoprite work t-shirts, they were stomp dancing, singing and shouting "Amandla Awetu" (Zulu for "power to the people," often used during anti-apartheid marches in the past). I asked a guy at Wimpy, the hamburger chain across the way, "what's wrong with them?" meaning, "why are they protesting?" "Oh, they're just doing aerobics," he answered.

- Once I first started offering kids around my house pieces of bubble gum they have often come to my window plaintively calling out "Chappies, please." (like an irritating teacher, I made them add the "please") Now they have progressed to shouting out daily requests for "malegere" (sweets), "penisela" (pencil), "blue-peni" (blue pen), "bugu" (book) -- pretty much anything they have ever seen in my bedroom that they would like to have. (Gum = "Chappies" brand made by Cadbury. Fruit flavored versions of Bazooka. And usually not stale. My favorite South African candy after Cadbury chocolate bars. I don't like Banana flavored Chappies, though. I give those to the kids)

- One of my teachers prefers wearing Safari vests to school over his dress shirt and pants. When I complimented one of them, he told me: "I can go without a tie. I used to see some people at the university wearing a tie but they are tsotsis (Johannesburg ghetto slang for "thugs"). Their hearts are not pure. They used to disguise themselves by means of wearing beautiful clothing. You do not need a tie to show that your heart is pure. It is inside.

- There are two versions of the Academy-award winning movie "Tsotsi" floating around here. They have very different endings. One is the official version. The other is a bootleg. I won't give details for folks who haven't seen the film yet. But it makes an interesting discussion as to why people here favor one version over the other. Here's a clue: one reflects the ending as it was written in the book by Athol Fugard and one does not. A reviewer for the Financial Times wrote:

...the film rejects the bleak ending of Fugard's novel by creating a space for redemption. [Gavin Hood, the director] suggests that it reflects the reality of the times. "In South Africa in the 80s, it felt hopeless. In the current political climate, in spite of epidemics, in spite of poverty, in spite of refugees fleeing war, it does not feel as hopeless as under apartheid. There is still some sense of hope."

Friday, July 28, 2006

It has been a very busy winter in South Africa – for me, anyway.

I am finally back to school after a three-week holiday (part of it spent in the Drakensburg Mountains of the KwaZulu-Natal Province) and one week at a remote village in Mpumalanga Province preparing for new Peace Corps volunteers (they arrived July 27).

In less than a week I will be gone again, accompanying the staff and students of one of my schools on a one-week trip to Durban (another place in KZN – along the coast of the Indian Ocean).

Many photos from this season have been posted on my Flickr site.

Holiday in the Drakensburg Mountains was lovely and cold. There was frost on the ground every morning and snow apparently fell on the higher peaks. This is Africa? Since most homes and hostels we stayed in don’t have heating systems and my travel buddy Emily and I had packed clothes more appropriate to the heat of Venda, we tried to find creative ways to stay warm. Luckily there were quirky little shops selling hand-knitted gloves and scarves, and pubs and restaurants with working fireplaces. Even one of the hostels in Pietermaritzburg had a fireplace in the bedroom that we kept fed.

I much prefer finding ways to stay warm than ways to stay cool. So, winter has become my favorite season in South Africa.

Our trip seemed to center around spirituality, although we didn’t completely plan it that way.

The first day we arrived in Pietermaritzburg, the capital of KZN (and a place where Gandhi was once thrown off a train for refusing to comply with segregation rules), we chanced upon a Pentecostal church service in the historic town hall. Although we were the only white folks present and were wearing street clothes, the church members warmly welcomed us. I tied Emily’s jacket around my head turban-style (she was already wearing a hat), as women were required to cover their heads.

Nearly every space on the wooden benches in the upstairs gallery and the main floor of the old fashioned hall was filled with men and boys in good suits and women and girls wearing white dresses with white hats or white head scarves. Much of the service involved long moments of singing and rhythmic swaying, which was meditative and hypnotic. Several church members shouted in ecstasy or grief during these times, as is common in Pentecostal churches. For me, the experience evoked a huge wave of love and compassion for every person in the room. Even though I couldn’t understand the Zulu words of the songs, I felt so connected and so blessed.

At one point during the singing I opened my eyes to see a girl, about 10 or so, with a silky cream colored dress tied in a bow in back and a gauzy cream colored head scarf, sneak from her seat next to her mother to stand next to Emily. She kept looking up at Emily in shy fascination during much of the service thereafter.

Mid-week, we attended a meeting of a poetry group in a cozy coffee shop near a university. The theme happened to be “spirituality and creativity.” Folks young and old, of a variety of races, sat in front of a warm fireplace and read aloud poems they had written, gave their thoughts on the subject or quoted from things they had read.

There was even a spiritual feel to Martizburg's Tatham Art Gallery, where a Klee and a Picasso were hung on the wall next to paintings by local African artists and there were no guards hovering about as we spent our time appreciating them.

The last part of the trip was a three-day retreat at the Buddhist Retreat Center in Ixopo, in the Drakensburg. The center provided a haven of quiet spaces, breathtaking views, enlightening reading, yoga, tai chi, meditation sessions, wonderful vegetarian meals and monkeys.

Last week I came full circle in my South African experience as I helped Peace Corps staff prepare for training a new group of volunteers. Remembering some of the angst and frustrations I had when I arrived nearly one year ago and knowing I had overcome most of it, made me realize that the country has become like home. It will be difficult to leave.

On the trip back to Venda, I stopped in Pretoria with some other volunteers to join the crowd of yellow-wearing fans to blow our vuvuzelas (horns), wave yellow and black flags and scream in joy as hometown heroes, Kaizer Chiefs, beat the famous English football club Manchester United (without David Beckham, one of its famous former players).

After the game, my friends and I found ourselves in an impromptu, enthusiastic street party as we walked the two blocks from the stadium to the backpacker’s hostel where we were staying. I lost my vuvuzela to the housekeeper at the hostel who wanted to keep blowing it at the revelers passing by long after we went inside.

I am finally back to school after a three-week holiday (part of it spent in the Drakensburg Mountains of the KwaZulu-Natal Province) and one week at a remote village in Mpumalanga Province preparing for new Peace Corps volunteers (they arrived July 27).

In less than a week I will be gone again, accompanying the staff and students of one of my schools on a one-week trip to Durban (another place in KZN – along the coast of the Indian Ocean).

Many photos from this season have been posted on my Flickr site.

Holiday in the Drakensburg Mountains was lovely and cold. There was frost on the ground every morning and snow apparently fell on the higher peaks. This is Africa? Since most homes and hostels we stayed in don’t have heating systems and my travel buddy Emily and I had packed clothes more appropriate to the heat of Venda, we tried to find creative ways to stay warm. Luckily there were quirky little shops selling hand-knitted gloves and scarves, and pubs and restaurants with working fireplaces. Even one of the hostels in Pietermaritzburg had a fireplace in the bedroom that we kept fed.

I much prefer finding ways to stay warm than ways to stay cool. So, winter has become my favorite season in South Africa.

Our trip seemed to center around spirituality, although we didn’t completely plan it that way.

The first day we arrived in Pietermaritzburg, the capital of KZN (and a place where Gandhi was once thrown off a train for refusing to comply with segregation rules), we chanced upon a Pentecostal church service in the historic town hall. Although we were the only white folks present and were wearing street clothes, the church members warmly welcomed us. I tied Emily’s jacket around my head turban-style (she was already wearing a hat), as women were required to cover their heads.

Nearly every space on the wooden benches in the upstairs gallery and the main floor of the old fashioned hall was filled with men and boys in good suits and women and girls wearing white dresses with white hats or white head scarves. Much of the service involved long moments of singing and rhythmic swaying, which was meditative and hypnotic. Several church members shouted in ecstasy or grief during these times, as is common in Pentecostal churches. For me, the experience evoked a huge wave of love and compassion for every person in the room. Even though I couldn’t understand the Zulu words of the songs, I felt so connected and so blessed.

At one point during the singing I opened my eyes to see a girl, about 10 or so, with a silky cream colored dress tied in a bow in back and a gauzy cream colored head scarf, sneak from her seat next to her mother to stand next to Emily. She kept looking up at Emily in shy fascination during much of the service thereafter.

Mid-week, we attended a meeting of a poetry group in a cozy coffee shop near a university. The theme happened to be “spirituality and creativity.” Folks young and old, of a variety of races, sat in front of a warm fireplace and read aloud poems they had written, gave their thoughts on the subject or quoted from things they had read.

There was even a spiritual feel to Martizburg's Tatham Art Gallery, where a Klee and a Picasso were hung on the wall next to paintings by local African artists and there were no guards hovering about as we spent our time appreciating them.

The last part of the trip was a three-day retreat at the Buddhist Retreat Center in Ixopo, in the Drakensburg. The center provided a haven of quiet spaces, breathtaking views, enlightening reading, yoga, tai chi, meditation sessions, wonderful vegetarian meals and monkeys.

Last week I came full circle in my South African experience as I helped Peace Corps staff prepare for training a new group of volunteers. Remembering some of the angst and frustrations I had when I arrived nearly one year ago and knowing I had overcome most of it, made me realize that the country has become like home. It will be difficult to leave.

On the trip back to Venda, I stopped in Pretoria with some other volunteers to join the crowd of yellow-wearing fans to blow our vuvuzelas (horns), wave yellow and black flags and scream in joy as hometown heroes, Kaizer Chiefs, beat the famous English football club Manchester United (without David Beckham, one of its famous former players).

After the game, my friends and I found ourselves in an impromptu, enthusiastic street party as we walked the two blocks from the stadium to the backpacker’s hostel where we were staying. I lost my vuvuzela to the housekeeper at the hostel who wanted to keep blowing it at the revelers passing by long after we went inside.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)